Home

A comprehensive resource for safe and responsible laser use

What should be done about laser pointers?

However, this webpage is in the “Perspectives & Opinions” section of the website. This page lists my personal suggestions. They are all based on my long experience since the early 1990s working in the area of laser/aircraft safety, and as one of the few persons who compiles stories and statistics on laser pointer misuse.

Here is a summary of recommendations to help reduce laser incidents and injuries:

- The best and fastest way to protect pilots and passengers is by pilot education and training. After training, pilots will know how to protect themselves and their aircraft. They will not overreact. Training is necessary because experience has shown that efforts on the ground have not and cannot end all laser pointing incidents. The pilot is literally the last line of defense, and thus needs the help and reassurance of training.

- This education and training can be done by individual pilots, pilot unions, and airlines. It does not necessarily require government involvement, although it would be best if aviation authorities required standardized training. Pilots, unions and airlines can take control of their own destiny instead of expecting this job to be done by others via bans, regulations, public education and laws which have proven to be of marginal help at best.

- Import and usage restrictions, stricter laws against misuse, and increased prosecutions may help somewhat. However, no one should think that these will significantly reduce laser/aircraft incidents at least in the short and mid-term. The experience of countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada, which have instituted restrictions starting as far back as 2008, have not shown significant decreases. In fact, in some cases, incidents have increased substantially after bans, restrictions, or new laws were put into place.

- Similarly, education efforts are not affecting the lasing rate. There are some indications that "getting the word out" may even cause incidents by persons who previously didn't realize lasers could reach aircraft, and persons who are anti-government or who disbelieve official information.

- Putting labels on lasers, warning about misuse against aircraft and persons, may help somewhat — but many people do not read or heed labels.

Here are a few additional suggestions:

- Consider a buyback program for laser pointers. This would be similar to gun buyback programs in some nations and U.S. states. It might be useful to begin with a pilot program in a city, state or region to see if this leads a significant reduction in laser/aircraft incidents and in laser pointer injury reports. Unfortunately, in many cases gun buyback programs did not significantly lower firearm crime rates.

- Hold regular meetings of persons in national aviation authorities (U.S. FAA, U.K. CAA, Transport Canada, CAA New Zealand, etc.) and others who are working to reduce laser/aircraft incidents. This would allow sharing of ideas, to discuss what programs are working and what are not. It also allows early warning if there are new types of lasers or misuse. (Existing groups such as SAE G10OL or ASC Z136.6 are somewhat similar in focusing on laser/aviation safety, and national aviation authority personnel are welcome to join. However these groups are primarily standards-based so much of their time is spent in wordsmithing standards documents.)

- Jurisdictions could require a pre-purchase test or signed agreement, so the buyer understands safe use of the laser pointer. At least one online laser pointer company required such a test before allowing their high-powered handheld lasers to be purchased. In February 2013, a North Myrtle Beach, SC ordinance required persons buying laser pointers to read and sign a short statement about hazards.

Details on many of these suggestions are below.

-

Mandatory pilot education and training

- Pilots should be required to have education and training in how to recognize and recover from a laser pointer incident. In the U.S., this should be mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration.

However, note that it is not necessary to wait for FAA. It could be implemented unilaterally by airlines. Also, pilot groups such as the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) could provide information to their members. Individual pilots can help themselves by reading information put out by FAA, CAA, ALPA, BALPA and other informed groups. (We have our own summary here.)

The best source of information about pilot education is the Aerospace Recommended Practice 6378, "Pilot Mitigation Against Laser Illumination Effects." A summary of this document, along with links to where it can be purchased, is here.

Pilot education and training would be the single most effective public safety improvement. That’s because pilots are the “last link” in the safety chain.

So it is essential that pilots know what to do if lased, and that they experience what a laser incident is like.

Fortunately, a 2003 FAA study showed that pilots exposed to bright laser flashes in a simulator were “inoculated” after one or two flashes. They learned how bad the flashes could be — and that they would not get worse.- It is not necessary to use laser light in the simulator. Tests with pilots in a cockpit who were first exposed to laser light, and then to the light from an inexpensive LED flashlight, showed that the flashlight can adequately simulate what the pilots experienced. More information is on the page How to safely simulate a laser strike.

- Similarly, it may not be necessary to use an expensive, full-motion simulator. One company, Lamda Guard, has experimented with a virtual reality aircraft simulator costing about $1000, so pilots can experience what a laser exposure is like. Again, a study would need to verify how much realism is needed — if this can be done relatively inexpensively.

Pilots also need to be educated so they will not panic or unduly worry. The chance of even a small retinal injury is minuscule, and the chance of severe injury is essentially impossible from consumer handheld lasers at aviation distances. After over 55,000 laser/aircraft incidents in five countries since 2004, there have been no confirmed, documented permanent eye injuries to pilots. (This is as of early 2020. In the past there have been some small retinal injuries that healed, and there have been some corneal injuries caused not by laser light but by the pilot mistakenly rubbing his or her eye too hard.)

Finally, it should be noted that most experts agree that a laser illumination on its own would not be sufficient to cause an accident. There would have to be some other factor, such as a tricky landing, or a flash during some other type of emergency. For example, imagine if someone on the Hudson River shore aimed a laser pointer at Capt. Sullenberger as he tried to land his USAir flight in the river, in January 2009. That would likely have turned the successful “Miracle on the Hudson” into a disaster. -

Better labels and user information …

- Governments should require pointers and handheld lasers to include a warning against aiming at aircraft. Language that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration currently suggests is “CAUTION - LASER LIGHT IS BRIGHT AND BLINDING - DO NOT SHINE AT AIRCRAFT OR VEHICLES AT ANY DISTANCE.”

Even a label with a shorter message such as “DO NOT AIM AT OR NEAR AIRCRAFT” could help.

(It may be useful to add that aiming at aircraft and vehicles is illegal. There needs to be a balance between a short simple message, and enough information to cause a person to actually heed the warning statement.)

In addition to labeling on the laser itself, more detailed information should be required in the user manual or a separate sheet. Some sample information sheets are here.

In the U.S., the FDA does not have the authority to warn against a bright light hazard. The agency does have regulatory authority to warn of health hazards to eye or skin — but not vision interference hazards. Therefore, a bill should be introduced in the U.S. Congress, specifically authorizing FDA to require an aviation warning label on pointers and handheld lasers, and also additional details in the user manual or on a separate sheet.

One reason for having such a label is the remarkable number of people who did not realize the hazard of aiming a laser at an aircraft, or that it is illegal. Even though many people will not read labels, it seems absurd not to at least give some warning.

In addition, it becomes easier to prosecute someone for knowingly aiming a laser at an aircraft, if the laser itself carries a warning against doing so. -

… and a more informative label

- It would be best to go beyond adding just an aviation warning, and to overhaul the FDA-mandated laser warning label. This will help with another growing problem — consumer laser eye injuries.

The current label was designed for technical users in a lab or in industry, not for relatively unsophisticated ordinary citizens.

Specifically, I recommend adoption of the proposed Laser Safety Facts label or something similar. This is basically a laser version of the FDA’s current Nutrition labels and Drug Facts labels. A Laser Safety Facts label would include more information on laser hazards, and provides guidance for safe use. A website and QR code is also proposed, where those who need full information — for example, someone who may have been injured by a laser — can easily find detailed answers.

This proposal is well-thought out and is “ready to go”. FDA would only need authority to implement this, just as they currently implement the Nutrition and the Drug Facts labels. Much more information is on the About Laser Safety Facts webpage.

This is a sample of the Laser Safety Facts label as it might appear on a high-powered Class 3B laser. The top portion, and “Avoid exposure to beam” text, are the same as an international standard laser warning label already used in countries outside the U.S. and which is legal for U.S. labeling. This label also adds a warning not to aim at aircraft, plus a website URL and QR code.

Click on the label to go to the webpage that is on the label’s URL and QR code (e.g., a webpage with more information about Class 3B laser safety).

Here is more information about labels for Class 3B lasers. -

Restrict high-powered consumer lasers …

- Reluctantly, over the past decade I have now come to the conclusion that there should be restrictions on consumer laser pointer and handheld sales. This was a very difficult decision. It was tipped by the doubling in U.S. incidents in 2015. Since we are not succeeding in educating laser pointer owners, we need to try a different and more severe tack.

(Even if, as I fear, doing so will not substantially lower the laser incident rate, at least — like Prohibition — it would have been tried. Those who advocate a ban or restrictions would have had their chance. And if the incident rate does not lower, then authorities would be forced to look towards other potential solutions, such as mandatory pilot training.)

There are a number of different approaches to a ban, licensing and/or restrictions. If I had to make a decision today, here is what I would propose. Note that these steps are for the U.S.; other countries may have different laws and challenges.

1) Reducing the power of a laser pointer from 5 mW to 1 mW. This puts the U.S. in line with other countries such as the U.K. and Australia. Lowered visibility should not be a problem. When the 5 mW limit was set, most pointers were red. Now, with the widespread use of green diodes, the visibility of a green 1 mW pointer is roughly equal to that of a red 5 mW pointer. (I will admit that this is a relatively minor change. There is not a huge difference between 1 and 5 mW pointers in terms of aviation or eye hazards. It is more symbolic than significant.)

2) Restricting the sale of consumer handheld lasers over 1 mW (e.g., lasers that are more powerful than pointers). A person wanting to buy one would need to apply for a permit or license. This could be standardized with a form stating the user's need, and perhaps a power limit for each broad type of need. For example, a laser used to point out stars by astronomy hobbyists should be capped at, say, 50 mW.

3) To cover costs, there would be a fee tor the permit or license. This could be a flat fee for processing — maybe $25 or $50 — and then an additional per-milliwatt fee, such as $1 or $5 per milliwatt. The license fee for a 10 mW laser, therefore would cost between $35 to $100. The license fee for a more powerful laser, such as a 500 milliwatt Class 4 laser would be between $525 and $2,550. If a person really wants a powerful handheld laser, and gives a reasonable justification, they could get one. But obviously the higher costs would discourage all but the most dedicated persons.

I should state here, incidentally, that I have not seen a good reason for an ordinary citizen to have a handheld laser over, say, 10 mW. Perhaps there are some specialized uses; if so, a licensing system can accommodate this. Also, for indoor private use such as a hobbyist laser show using non-portable, non-handheld lasers, there should be no restrictions. These have not proven to be a problem. The issue is that too many people are using higher-powered handheld lasers outdoors, with ignorance or malice against aircraft.

Another advantage of restricted sales is to help reduce eye injuries caused when a person aims a laser beam at themselves or someone near them. Injuries from these are rare, especially compared to other ways that ordinary objects can injure people. But reports of such incidents and injuries have been rising since 2015. One way to slow this rise is to make it harder for regular people to obtain lasers over 1 mW.

At this time (2018) I would not make private possession illegal. I have a feeling that it is new owners, more than established ones, who are more likely to aim at aircraft. Additional studies on persons arrested should be done to see if there is a link between time-of-purchase, and time-of-illegal-use.

One idea is to treat high-powered lasers like switchblades or other illegal knives, where possession in public is illegal. If high-powered lasers are in your own home for private use, no one should take them away. But if they are seen in public, the police or others should be empowered to permanently confiscate them, without any other fine or arrest.

Public confiscation was implemented on a geography-limited basis in Canada starting in mid-2018. It would be interesting to see if this has any noticeable effect on the aircraft lasing rate.

It is vital to note that any ban or restriction must be crafted carefully. This is to avoid unintended consequences or loopholes. To give just one example, there should not be a way to sell kits of laser diodes plus housings so a person could easily make their own battery-powered handheld. Also, there may need to be restrictions on resale, such as not allowing any sale by individuals (e.g., on eBay). Again, these details need more thought and study.

(A reader made an interesting suggestion I’ll repeat here: “It should be technically possible to ‘pulse code’ each new laser pointer so that the beam encodes a traceable serial number so that ownership could be traced. Aircraft could carry a sensor that decodes and records the ID information, passing it on to Law Enforcement.”) -

… but don't rely on a laser ban (alone) to prevent laser misuse

- No one should think that a ban on laser sales and/or possession will magically stop the problem. Unfortunately, laser pointer misuse will still occur.

This chart shows Australia’s experience. In mid-2008, government banned both the sale and the possession of laser pointers above 1 milliwatt. Yet the number of pilots reporting illuminations actually rose for the next four years. The numbers have since decreased somewhat, but as of 2015 in Australia there are almost 4 times the number of illuminations as before pointers were banned.Although Australia's absolute number of incidents is lower than the U.S., this is not the case if we take into account that the U.S. has nearly 14 times more people than Australia. The chart below shows the number of incidents in Australia on a per capita basis.In fact, Australia had more laser incidents, on a per capita basis, than did the U.S. up until 2015. This is despite the mid-2008 ban on laser sales and possession in Australia.

A similar result has been seen in New Zealand. On March 1 2014, lasers over 1 milliwatt were banned from importation and sale. Yet the rate of lasing aircraft rose from around 104 incidents in 2014, to around 169 in 2017.Canada's experience also shows that restrictions do not significantly lower lasing rates. In June 2018, Transport Canada banned non-work or education use of hand-held lasers 1 milliwatt or more (the power of a small pet laser pointer) in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, and within 10 km of airports or heliports. But according to the National Post, there were 274 incidents in 2019, which was a 21% increase over the 226 incidents in 2018, the year the ban was instituted.

The conclusion is that new restrictions or a ban on laser pointers, alone, probably will not significantly bring down the number of laser incidents — at least not for many years. This is not to say a ban shouldn’t be considered. But a ban shouldn’t be relied on as the only way to reduce the number and severity of laser incidents.

Plus, even if laser pointer sales could be completely shut down, there would still ways for people with malicious intent to make or get higher-powered lasers. For example, it would be trivial to obtain a high-powered laser that is portable, or to make it portable. Again, in such a case the pilot would be the last line of defense, to prevent a laser illumination from causing a tragedy. -

Laser eyewear for some pilots …

- The use of Laser Glare Protection eyewear is not recommended as routine. If laser light is reported or suspected in an area, then a pilot may wish to put on LGP eyewear that has been previously tested in the cockpit (on the ground) to ensure the LGP does not block critical indicators, displays and airport lights. First responders such as police and rescue pilots would benefit the most. This is because they may be required to fly into a potentially hazardous laser situation in order to identify a perpetrator, or to continue a rescue.

The most common color seen in FAA incidents is green, representing almost 95% of incidents each year. As of 2016 there is only one common green wavelength, 532 nanometers. Therefore, any eyewear that can reduce the intensity of 532 nm light would potentially be useful in 95% of illumination situations.

However, it is vital to note that any eyewear that can block certain laser colors will also block that same color from instrument panel lights, display screens, and airport lighting. This means that having pilots wear laser glare protection glasses at night could be more hazardous than if they experience a laser illumination. After all, it’s relatively rare for any given pilot, on any given flight, to have laser interference. But pilots always need to see their instruments.

Manufacturers of Laser Glare Protection eyewear for pilots generally want to have a narrow band of green being blocked (e.g., centered around 532 nm). This allows other greens on the instrument panel to be seen.

One potential disadvantage in the future is that laser pointers with 520 nm light will become more prevalent. LGP optimized for 532 nm would provide no real protection — and LGP optimized for both greens would have a greater problem with instrument panel visibility.

An individual pilot can purchase LGP eyewear if they wish. Also, some pilot groups such as a police department’s aviation division may want to adopt these. They should do so only after night ground testing, in the cockpit to be flown, to see whether there is any undesirable color loss in vital indicators and displays. -

… and consider using anti-laser windscreen film

- One promising approach is to put a Laser Glare Protection film on the inside of an aircraft’s windscreen. At least two companies, Metamaterial Technologies Inc. and BAE Systems, are working on this. Two key advantages are:

1) protection is automatic — pilots do not have to do anything special like put on glasses

2) film on the windscreen cannot interfere with pilot color identification of cockpit instruments and displays (unlike wearing green-blocking glasses).

There are a few disadvantages as well. The film may be costly — many thousands of dollars — to install in a cockpit. It would almost need to be required by national aviation authorities (e.g., FAA, CAA) in order to force airlines to spend the extra money to use the film. It requires significant testing and review to become certified as airworthy; unlike pilot glasses which can be worn or not worn at a pilot’s discretion. And it may protect only against certain wavelengths. A determined perpetrator could simply use an unusual or new wavelength, rendering the film useless.

But some help is better than none, especially when about 95% of current (2017) laser illuminations are from a single wavelength, 532 nm green.

Windscreen film should be evaluated for future use. But it cannot and should not be considered to be a total solution. Pilots still will need to know how to recognize and recover from any lasers whose wavelength and/or power cannot be significantly reduced by the film. -

Continue prosecuting laser offenders

- For a while, it was hoped that publicity about laser offenders, their arrests, and their convictions would help deter people from pointing at aircraft. This seemed to work from about 2011 to 2014, when the increase in incidents leveled off at about 3,500 to 4,000 per year.

But in 2015 the yearly rate nearly doubled. The rate continued to be high in 2016 and 2017.

In 2015 there was no apparent change in laser technology, sales, or prosecutions/convictions. Therefore it seems as if the publicizing of arrests is not helping to lower incidents. In fact, more study may show that publicity causes a “copycat” effect.

Based on the current evidence, prosecutions of laser perpetrators should continue. However, there is no indication that this is a significant factor in reducing the rate or increase of incidents.

One reason may be the low rate of arrests and convictions. A 2014 study by Cyrus Farivar, summarized here, found that less than 1% of reported laser/aircraft incidents led to an arrest, and less than 0.5% of incidents led to convictions.

An ordinary person, who truly did not understand the hazards, should not be jailed. But antisocial persons who deliberately target aircraft, often along with other illegal activity such as drug use or parole violations, should receive harsher treatment including jail time. -

Comments on Sen. Schumer's Feb. 2016 proposals

- Since August 2012, Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) has asked the Food and Drug Administration to restrict higher-powered handheld lasers, and to require aviation warning labels on lasers. He repeated this in March 2015 and November 2015. On February 3 2016, Schumer met with the FDA commissioner nominee, who agreed to consider having the FDA ban high-powered green pointers. (See here for a list of Schumer-related stories.)

While Sen. Schumer’s interest is appreciated, the Senator should be aware that under current FDA regulations (21 CFR 1040.10 and 1040.11), the agency does not appear to have the authority to implement his requested changes. It would be easier if the Senator introduced a bill giving FDA the necessary authority — and just as important, the funding to make any restrictions meaningful.

The FDA division responsible for laser safety, the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, is underfunded in the laser regulatory areas. Many Americans feel that government should be smaller; however, for those like Sen. Schumer who want increased safety this also means increased staffing to regulate and enforce labeling requirements and sales restrictions. -

Comments on FDA's Oct. 2016 proposal

- On October 25 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration proposed to designate all laser pointers that are not red as “defective.” This designation would prohibit U.S. sales of green, blue and other non-red pointers and would make it easier for FDA to control and seize imports of such lasers.

As of December 2018, there has been no update on this proposal; it may no longer be active.Pros and cons of the proposal

A major feature of FDA's proposal is to simplify regulation. Inspectors, police, customs, etc. can simply restrict or confiscate laser pointers based on color. There is no need to measure the laser output power.

There are some caveats, however.- It is a stretch to call laser pointers "defective" under law simply because their color is green or blue rather than red.

- While red handheld lasers historically have been relatively low power compared to green or blue lasers, this may not always be true. In the future it may be possible to make low-cost, high-powered red handheld lasers.

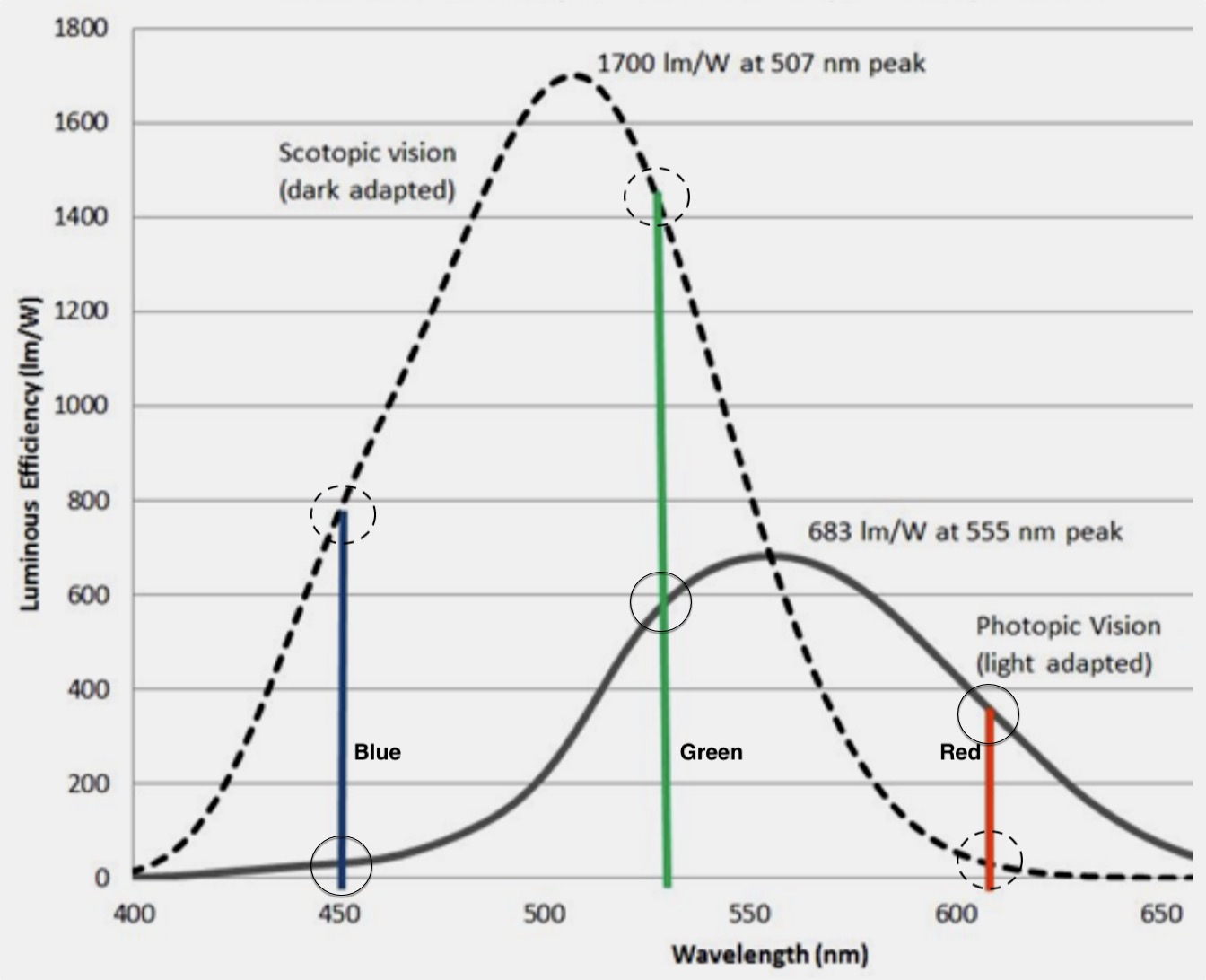

- FDA's rationale is based in part on how visible red lasers are to pilots, compared to equal-power green or blue lasers. They used data assuming pilots flying at night have completely dark-adapted vision (scotopic curve). However, pilots are looking at their cockpit screens and lights, plus they view the lights of the city outside. Their vision is actually closer to light-adapted. Recognizing this, the aviation advisory committee SAE-G10T and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) both use normal light-adapted vision (photopic curve) to determine how color affects apparent visibility. When the FDA data is analyzed using the SAE and FAA curve, the difference between red and green light is not as great; thus weakening the FDA's analysis.

Chart adapted from FDA presentation. FDA says that during nighttime, pilots have dark-adapted vision. Therefore, FAA uses the dashed Scoptic Vision curve to compare blue, green and red visibility (assuming equal power lasers). Looking at the dashed circled areas, FDA says that red "at 615 nm and longer, viewed with night-adapted vision, appears only 1.4% as bright as green at the commonly manufactured 532 nm."

However, SAE and FAA determined pilots have light-adapted vision. They use the solid Photopic Vision curve. Looking at the solid circled areas, red at 615 nm appears 50% as bright as green at 532 nm. This undercuts FDA's argument that red lasers appear much dimmer than green lasers to pilots.

In conclusion, while the FDA proposal is clever and deserves consideration, it may not fit the legal definition of "defective," it may not be future-proof, and it may not be technically sound (e.g. based on relevant analysis of pilot vision effects).

A story summarizing the FDA's proposal is here. A detailed 10-page paper discussing the proposal, co-written by an FDA expert, is here.

Note: All data above is as of February 15 2016, with a minor update June 28 2018.