Home

A comprehensive resource for safe and responsible laser use

Fast laser pointer facts for media

-

Laser pointer hazards - aviation

- The main hazard for aviation is that pilots can be distracted or temporarily flashblinded by the light from a laser beam, as explained in more detail on the Laser hazards to aviation page and the Basic principles of laser hazards page. At aviation distances (being many hundreds or thousands of feet in the air), laser light from the ground is a large, windscreen-filling “blob” —unlike the tiny dot a laser makes at close range.

If the laser light is strong enough, pilots may also suffer temporary eye effects such as eye irritation, tears, headache or pain.

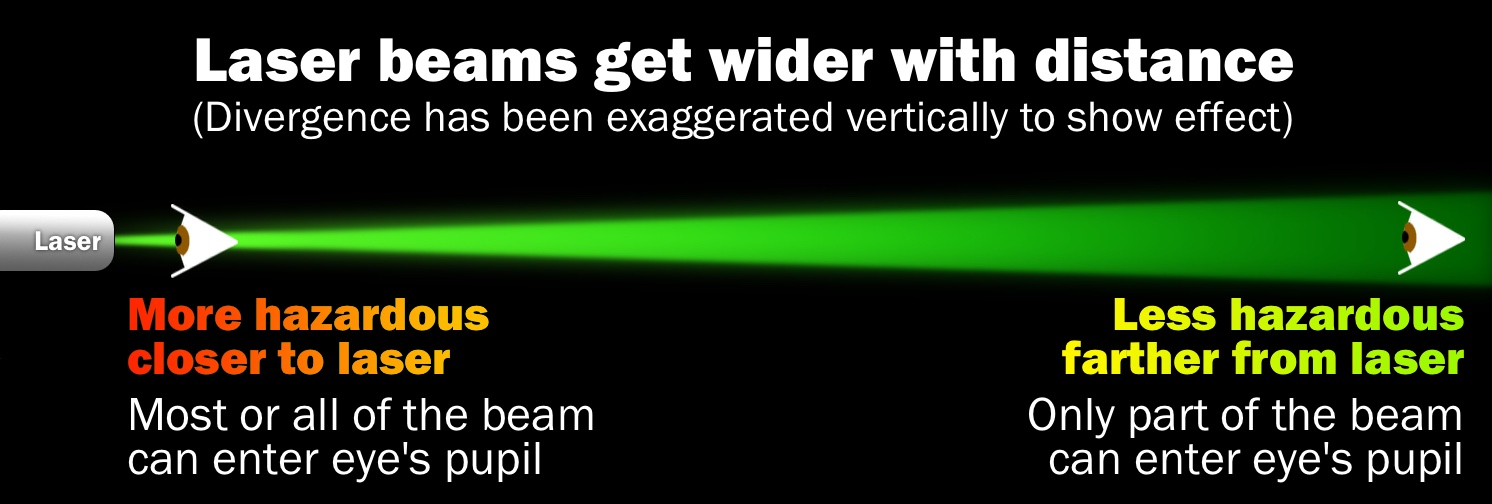

Public domain photo from the U.S. FAA, showing how a laser beam spreads over long distances and can fill the windscreen. The FAA’s highest-resolution version is here.Fortunately, hazardous laser effects which can occur at close range, such as cutting or burning materials, cannot happen at longer ranges of hundreds or thousands of feet as occur during ground-to-air laser incidents. This is because over such distances a laser beam spreads from a concentrated dot to a large diffuse glow, thus spreading the laser’s power over many square inches or feet.

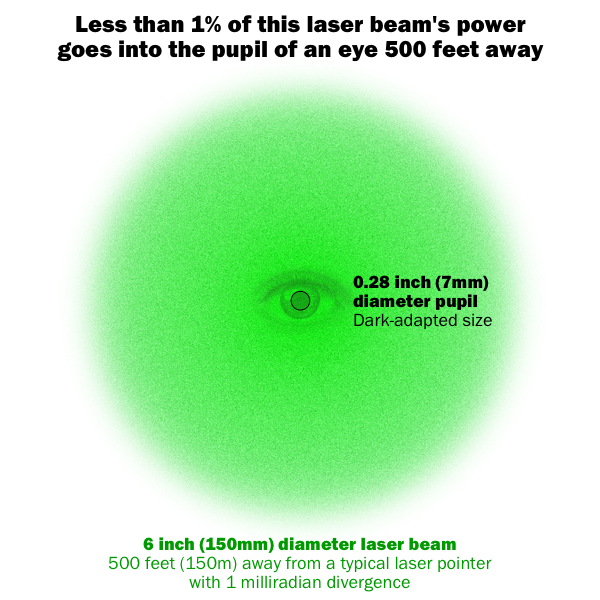

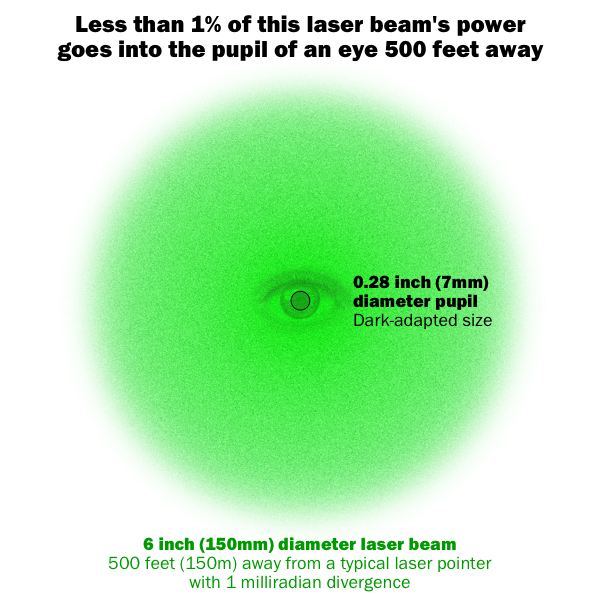

In the United States, the minimum altitude for aircraft flight is 500 feet. Of course, aircraft land and takeoff, and helicopters often fly or hover lower than 500 feet. But let’s look at how much a laser beam spreads if it was aimed at an aircraft 500 feet away:

Because the light is so spread out, experts say it is unlikely that pilots could have a serious or permanent eye injury.

As of January 1, 2026, there have been no documented or proven permanent eye injuries from any of the over 117,000 laser incidents reported to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration since 2004. More specifically, FAA spokesperson Alison Duquette told LaserPointerSafety on March 19 2015: “The FAA is unaware of any U.S. commercial pilot who has suffered permanent eye damage as a result of exposure to laser light when in the cockpit.”

In addition, there have been no documented or proven permanent eye injuries from over 30,000 laser incidents reported in other countries including the UK, Australia, Canada, Italy, Sweden, New Zealand and Japan. For example, on July 26 2017, Transport Canada spokesperson Julie Leroux told LaserPointerSafety that “Transport Canada is not aware of any cases where a pilot suffered permanent eye damage as the result of a laser strike."

In a very few cases, pilots have claimed to have an eye injuries, such as "corneal burns." However, visible laser light would only damage the light-absorbing retina since visible light passes through the clear cornea and lens without any effect. Such injuries were self-inflicted by the pilots rubbing their eyes too hard and scratching their own corneas.

Laser experts who studied other claims of significant or permanent eye injuries have not confirmed that the pilots' eye conditions were caused by laser exposure. More details are below in the section "Why pilot reports of injuries may not be accurate".

It can be difficult for medical personnel without laser lesion experience to properly identify the cause of retinal abnormalities; for example, whether an injury was pre-existing. Any report of a ground-based laser causing a retinal burn or lesion to a pilot would be exceptional, and should be independently verified by laser eye experts.Number and type of aviation incidents

FAA requires pilots to report any laser sightings in the U.S. In 2025, there were 10,993 aircraft that reported seeing lasers. Additional statistics for the U.S. and other countries are here.

Based on a mid-2011 study of FAA reports, most lasers -- 73% of the incidents -- were outside the aircraft and did not enter the cockpit. In 81-95% of the incidents, the laser was not tracking the aircraft. This means that only 27% of incidents had laser light on or through the windows, and only 5-19% (the study is unclear) were deliberately aiming for the aircraft. Pilots reported eye effects or injuries in 1.5% of the incidents. Serious or permanent confirmed eye injuries are rare (see below for more on “Why pilot reports of injuries may not be accurate”.)Also illegal to point at drones

FAA considers drones (unmanned aircraft systems) to be aircraft. Since it is illegal to aim a laser pointer at an aircraft, or the flight path of an aircraft, in U.S. airspace, then it is also illegal to aim at a drone.

One reason is that the laser light can interfere with the view of the drone operator, or could possibly damage the camera's sensor which can then make it difficult or impossible to safely fly the drone. -

Laser pointer hazards - eye injuries

- As discussed above, there is a very small likelihood of laser pointers causing an eye injury to a pilot. Unfortunately, pointers have caused eye injuries to persons misusing them by aiming them into their own eyes, or the eyes of someone nearby.

Serious/permanent eye injuries

Only a few serious or permanent eye injuries per year worldwide are reported due to consumer lasers. Many or most of these turn out to be self-inflicted; for example, a teen tries to have a “lightshow” in his eye.Temporary/minor eye injuries

There are a larger number of laser pointer-caused minor eye injuries. Again, many or most are self-inflicted.

Often these will heal over time, or the spots will have no adverse effect on vision. The brain can "fill in" small spots so they are not noticeable except when looking at a uniform blue sky or white wall.

There are some media reports and hospital reports of incidents resulting in temporary effects such as eye irritation, spots, or headache. But these are not the same as doctor-confirmed serious or permanent injuries.

For more information, see the page with Consumer laser eye injury info. -

Laser pointer hazards - riots and demonstrations

- Beginning in the late 2000’s, some protesters have taken to using lasers against security forces; a sample list is here. Tactics include distracting and temporarily flashblinding the police officers. Because lasers are used at close range and are aimed at eyes, in a confrontational situation there is more potential for serious or permanent eye injury.

More information on laser use during protests is here. -

Why do people misuse laser pointers?

- Regarding aiming at aircraft, a review of arrests and convictions shows that there are two general types of misuse.

- One is misuse by the general public, who are “playing around” with their lasers. Many ordinary citizens who were arrested have said that they did not realize the hazard. Often, aiming towards aircraft is done because of a visual illusion where a laser beam can seem to end so it looks as if it cannot touch an aircraft. Also, users may think that the beam won’t be seen by the pilots: it is “under” or “behind” the aircraft. Finally, even if the beam is aimed at the cockpit, users may think the beam makes a tiny dot of light on the windscreen just like when they play with their cat or highlight a PowerPoint slide. They don’t realize that over hundreds of feet, a laser beam spreads to become a 2-3 foot “blob” of light that blocks pilots’ vision.

- The other type of misuse is by antisocial or criminal persons. They may not like police, or the noise of airplanes and helicopters. (For example, a man in Orlando hit aircraft over 23 times in a three-month period; he had previously filed 500+ noise complaints with the airport.) They may already be involved with illegal activity such as possessing drugs or being in a stolen vehicle. In a few cases, the laser may be deliberately used in order to interfere with a police helicopter’s crime-fighting activities.

-

Ways to improve safety

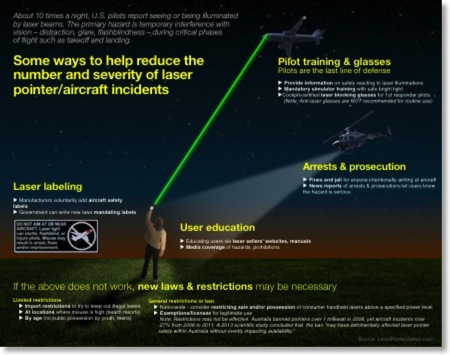

- One way to help improve laser/aircraft safety is user education. Media can help by reminding laser owners that they should NEVER point at or near an aircraft, or other vehicle, or a person’s head.

Incidents can be reduced if users know that (1) a laser pointer beam can definitely reach aircraft, (2) at a distance, the beam spreads so much that it can distract or flashblind a pilot, and (3) aiming at aircraft is illegal and many people have been arrested and jailed. It is very helpful if media stories make these points clear. This hopefully helps reduce the number of incidents. Also, as awareness increases, the legal excuse that “I didn’t know it was dangerous” becomes less valid.

User education is important, but it is not the only solution. For various reasons, there is no single magic solution (“Warning labels!”, “Pilot goggles!”, “Banning pointers!”).

To reduce incidents, a multi-pronged approach is necessary. And for real, meaningful safety improvements, pilot education and training is essential. You can read more about various ideas to improve safety on the How to reduce incidents webpages.

This diagram shows various ways to help reduce laser pointer incidents. Click to enlarge.

If you are interested in legislative and regulatory solutions, see our webpage If you are writing a laser law. -

Laser incidents, statistics and laws

- LaserPointerSafety.com has three news pages which cover aviation-related incidents, non-aviation incidents, and all other news. For example, we have the latest statistics about aviation incident numbers, and coverage of newly-proposed laser laws from the U.S. and other countries. (Separate pages list already-existing international and U.S. laws.)

We also have a page listing the sentences given to persons for laser misuse. This is a kind of “rogue’s gallery” that shows how seriously officials take these incidents.

You can also click on the blue links at the right-hand side of any of these four pages to find specific categories of news items such as aviation-related arrests, non-aviation arrests, news from locations such as the U.S. or California, and many other classifications.

This diagram shows how to scroll down to find General categories, Year of posting and Specific subject tags.

Or you can go to the bottom of the Index to news stories page to see a quick way to find all categories and tags for each of the three news pages plus the "Sentences for laser offenses" page. This might be an easier way to find specific articles or to research specific topics.

-

Finding videos of laser pointer incidents

- Some news stories here at LaserPointerSafety.com include videos of laser pointer misuse, or have links to such videos. Here are links to stories with videos for aviation incidents, for non-aviation incidents, and for other laser pointer news.

In addition, search YouTube or similar using a search phrase such as "police helicopter laser". You should — unfortunately — be able to find many videos taken from an aircraft where a laser beam is pointed directly at the aircraft. Some of the videos also include footage from the air of the suspect being arrested by officers on the ground.

The FAA has a 21-minute video which contains brief footage of a pilot (safely in a simulator) being illuminated by laser light. The video is a bit unrealistic in that it shows a constant laser beam on the pilot's face:

In real life, a handheld laser from the ground can never be that steady. Instead, the pilot would have occasional light flashes in his or her eyes. This is demonstrated if you do a YouTube search as described above to see what a actual laser illumination looks like from a flying aircraft.

-

FAQs and other information

- General questions are in our FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) webpage. A few laser enthusiasts seem to doubt that the aviation problem is real, so we have made a special FAQ for doubters webpage.

Finally, if you have questions or concerns that are not addressed by the FAQs or our many other webpages, please feel free to contact us using the link at the bottom of this webpage.

-

Camera caution for TV and press news crews

- Be very cautious if you aim a laser pointer beam directly into the lens of a video or still camera. While many reporters have aimed low-powered consumer laser pointers into a broadcast camera with no ill effect, it is possible for a camera sensor (CCD or CMOS) to be permanently damaged by too-bright laser light. This can cause dark spots, or the loss of one or more rows of sensors.

Still camera sensor damaged by multiple direct beams at various laser shows. Note that this does NOT represent how a human eye’s vision might be damaged in a consumer laser incident. Photo of an HP Photosmart 945 5 megapixel camera courtesy Aljaž Ogrin. Click for larger view.

In a very general sense, camera damage is similar to how the human eye can be damaged if overloaded by too-bright laser light staying in one area of the retina for too long. However, sensors vary widely in how susceptible they are to being damaged. Informally we have found that camera sensors are much more sensitive than the eye, although we are not aware of any scientific study. So, just because a particular camera sensor may be damaged by a laser pointer, does not necessarily mean that a human eye having the same exposure at the same distance would be injured.

It is possible to aim a laser directly into a camera lens if you take precautions. Standard laser pointers in the 1 mW to 5 mW range probably will not cause problems, especially if you keep the beam moving. For more powerful pointers, put the camera tens or hundreds of feet from the laser source. The beam’s intensity will be spread out so the chance of damage is much smaller. (At long distances, this also more accurately depicts the large “blob” light source when an aircraft is illuminated by a laser that is many hundreds or thousands of feet away.)

Finally, consider using an inexpensive consumer camera such as a GoPro. If there should be any damage, the replacement cost would be minimal.

For more information, see the webpage If your camera is hit by a laser beam.

Media-specific issues

(inaccuracies which are often misreported)

-

Laser hazards up close are NOT the same as at aircraft distances

- Sometimes a reporter will show a thin laser beam burning or popping something close to the laser. But a laser beam at aircraft distances is much wider (on the order of a foot or two). Because the light is so spread out, it could not burn materials or pop a balloon. Instead, the primary threat to pilots is a laser being a relatively wide light that can distract, can obscure vision (“glare”) or can temporarily flashblind a pilot.

Therefore, it is not accurate or fair to show a thin beam close up, without making it clear that the same beam at the aircraft is much wider (like a flashlight) and much less powerful (it could not burn things or pop balloons like it can up close).

This demonstration above is inaccurate. A reporter stands just a few feet from a helicopter, and aims it through the windscreen at the camera. Because he is so close, the beam is a thin red line as he moves the laser around. As you see, the small diameter does not obscure vision. But in a real in-flight illumination, the laser beam spreads to many inches or feet in diameter, as shown below:

-

Laser safety distances are not the same as laser hazard distances

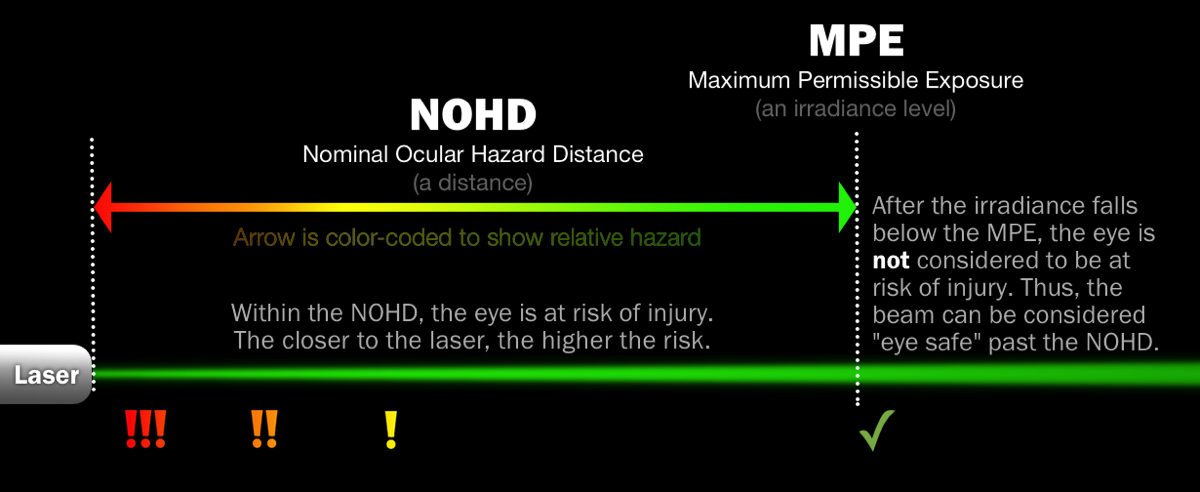

- Laser safety experts have developed ways to analyze a laser and determine an exposure and distance that can be considered safe. These concepts are called the Maximum Permissible Exposure (MPE) and the Nominal Ocular Hazard Distance (NOHD).

- The MPE is the highest concentration of light (irradiance) that is considered safe for a given exposure time. For an accidental, unwanted exposure to continuous wave visible laser light where a person naturally blinks and/or looks away, the MPE for a 1/4 second eye exposure is 2.5 milliwatts per square centimeter.

- The NOHD is the distance from the laser at which the beam's irradiance level first falls below the MPE. In other words, the NOHD is the distance from the laser where a detectable change or injury is considered extremely unlikely for the given exposure time.

A key concept is that laser beams spread out. The further a person is from a laser, the larger the beam diameter. As the diameter becomes larger than a human pupil, then less of the original laser light will be able to enter the eye. Here's an example: The Nominal Ocular Hazard Distance (NOHD) is simply the distance from the laser source at which the exposure falls below the Maximum Permissible Exposure level:

The Nominal Ocular Hazard Distance (NOHD) is simply the distance from the laser source at which the exposure falls below the Maximum Permissible Exposure level: For example, a very low-powered 1 milliwatt laser pointer has an NOHD of 23 feet (7 m) while a powerful 100 mW handheld laser has an NOHD of 230 feet (70 m).

For example, a very low-powered 1 milliwatt laser pointer has an NOHD of 23 feet (7 m) while a powerful 100 mW handheld laser has an NOHD of 230 feet (70 m).

A non-expert might think that this means these lasers will cause eye damage 23 (or 230) feet away.

But this misstates the NOHD concept.- First, there is actually a safety factor built into the NOHD. It is conservative, so a person could be well within the NOHD (closer to the laser) before any detectable change happens to the retina.

- Second, the NOHD is based on experiments where the laser and the target (a monkey's eye) are fixed in place at a short distance. This is not the same as in a situation such as aiming at an aircraft, or at a police officer in a protest, where the laser is much further from the target (the beam has spread out) and both are moving relative to each other (spreading out the laser beam's heat).

- Finally, the NOHD was determined based on the smallest visually detectable change to the retina. It is likely that such a small injury would not be noticed or would heal.

For these reasons, police, pilots, the press and others should not imply that eye injury will occur at the NOHD distance. Scientists do state that, if a person must be exposed to laser light, then it is considered safe to do so past the NOHD. But they do not say that at the NOHD distance, injury will occur.

Under best conditions (fixed laser and target at close range), at 1/3 of the NOHD there is a 50/50 chance of causing the smallest visually detectable change to the retina. To cause a serious or permanent retinal injury under best conditions, a person would have to be even closer to the laser. And this would be unlikely if the laser and target were constantly moving relative to each other.

That is one reason why as of January 2026, there have been no known serious or permanent eye injuries to commercial or general aviation pilots. (There may have been injuries to military pilots in combat zones but if so, this information has been classified.)

For more information on the NOHD and the "injury distance" ED50, see this page. -

"Illegal laser pointers" are not illegal to own - in the U.S.

- Often you will hear about “illegal laser pointers.” Technically, in the United States this means the manufacturer or seller did something illegal.

In the U.S. it is NOT illegal for a person to own a laser, of any power, under federal law (there are exceptions in a few states and localities).

More specifically, lasers 5 milliwatts (5 mW) or more are not supposed to be marketed or sold for pointing purposes. This is why Internet sites often promote higher powered lasers for burning, balloon-popping or other non-pointing uses. But if someone buys a laser that is above 5 mW, there is no federal law against possession or use.

For more information, we have a description and analysis of FDA authority over laser pointers and handheld lasers, and a list of some state and local laws which may make possession illegal in certain cases such as that of minors.

In Australia, parts of Canada, and some other countries or locations, it may be illegal to possess a laser pointer in public without a specific reason or permit. We have a list of international (non-U.S.) laws. -

Why pilot reports of injuries may not be accurate

- It is very difficult for consumer-grade pointers and handheld lasers to cause eye injuries at aircraft distances. The beam is spread out (thus dramatically lowering the irradiance or “amount of power entering the eye”), the beam is hard to keep on a far-away target (heat cannot build up), and the pilot can blink or look away (an uncooperative target). For these reasons, many laser safety experts are skeptical of pilot injury reports. A 2016 report by three top U.K. laser experts explains why this is the case.

Scientists know how much laser power is needed to damage the retina. Almost always, the laser exposure at the pilot’s location is well under the required power.

The only eye structure that can be damaged by consumer-grade pointers and handheld lasers is the retina. This is where visible light is absorbed. So the first question is “Was there retinal damage?” The next question is whether the damage is new (caused by the laser) or is due to a pre-existing bright light exposure. (One pilot reported a laser injury but it turned out to be sunburn from a few weeks earlier). In addition, minor retinal damage often is repaired by the eye in the same way that a small cut or burn on the skin can heal with no adverse impact. So another question is “Is the damage permanent?”

Pilots have reported headaches, corneal scratches and other maladies which cannot be directly caused by laser pointers. Certainly pilots should not have laser light aimed into their eyes, and if they do have secondary maladies this is unfortunate. But having a headache, or rubbing one’s eyes after an exposure is very different from claiming severe or permanent eye (retinal) damage from a laser. Be careful in your reporting to differentiate these.

Again, we are not saying that it is OK to aim lasers at pilots, or that pilots are not justifiably upset when they get flashed. Certainly, vision-blocking and distracting lasers are a genuine hazard to safe flight. But we are saying that what pilots fear most -- permanent eye damage -- is simply not true as of this writing in mid-2021, at least for commercial pilots in the U.S. If military pilots have been injured in a war zone or conflict area, this information would probably be classified.

For more information on how lasers can damage eyes, see the pages Don’t aim at head and eyes and If you are hit by a laser. For more information on pilot reports of eye effects and injuries, see the section United States - Eye effects and injuries.

Who we are

-

About this website and the author

- The author of this website, Patrick Murphy of Orlando, Florida, has worked in the area of laser/aviation issues since the early 1990s. He sits on industry committees dealing with laser safety issues, and has helped write documents used by and for the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. Contact information and a detailed biographical background is on the About LaserPointerSafety.com page.

The website was started in 2009 to inform the public, media, regulators and others about the complex issues related to laser pointer safety, and especially laser/aviation safety. The website is privately funded. The website is not done for financial gain; the main objective is to provide information including studies and news reports.

The website author has no financial interest in laser pointers. If they were banned tomorrow it would not affect his income sources or safety-publicizing efforts.

Beginning around 2022 the website was updated much less since incidents kept occurring (and even increasing) but there seemed no urgency to change the status quo.